The Artist’s Way: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton

I first came across the photographs of Rosemary Gilliat Eaton about 10 years ago, when I was looking up images on the website of Library and Archives Canada. I was working on a project for which I needed old photos, and I wanted to see what they had available in their online catalogue.

If you’ve never snooped around LAC’s photo bank, there’s a lot to take in. I’ve since joyfully wasted numerous afternoons typing in random words in their search engine just to see what would pop up. “Women talking”, “cowgirl”, “cake”—it’s a kind of slot-machine for old photos, and you never know quite what you’re going to get.

Portrait of Rosemary Gilliat Eaton, Shilly Shally Lodge, Gatineau Park, Quebec

Anyway, despite the thousands of images in their bank, I noticed that nearly every time I came upon an image that really spoke to me, it had been taken by someone named Rosemary Gilliat Eaton. At the time, I knew nothing about Rosemary expect that I was really moved by her work. There was a joy and sensitivity to her photos, and I recognized in them something that felt familiar to me, a feminine quality that seemed to reveal a lot about who she was.

Her images had a way of capturing small, intimate moments: women laughing together, a glance exchanged, hands at work. They weren’t just beautiful; they felt lived-in, warm, and deeply human.

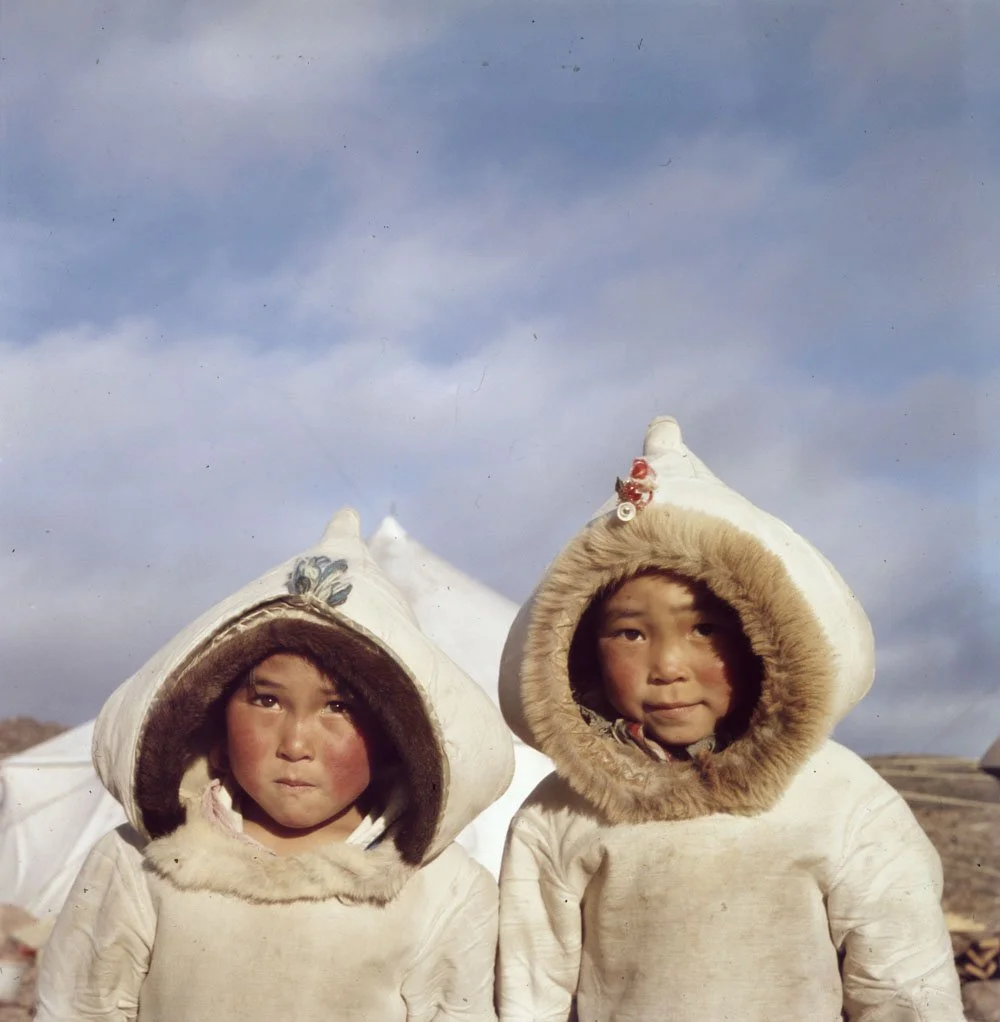

Born in the UK in 1919, Rosemary moved to Canada in 1952 and quickly became one of the country’s most compelling documentary photographers. She traveled extensively, camera in hand, capturing everyday life across Canada, from the Arctic to the Maritimes. But what set her work apart wasn’t just the places she documented, it was the way she saw people.

In her images, I get the sense that she wasn’t just passing through. She was present and engaged. Whether she was photographing a woman adjusting her hat in a mirror, a child playing outside in the cold, or a group of friends in Gatineau Park, she managed to bottle up fleeting moments of joy, thoughtfulness, and intimacy. Her work has a timeless quality, not because it’s nostalgic, but because it feels immediate, as if you could step right into the frame.

It’s also inspiring to think of how she carved out space for herself in a male-dominated field. At a time when photojournalism was largely defined by a hard-edged, sometimes detached gaze, Rosemary’s work felt deeply personal. It was full of care. She wasn’t just documenting life; she was honoring it.

I still find myself drawn to her images. I still pause when I come across one, still feeling the same sense of recognition I had when I first discovered her work. There’s something special about a photographer who can make you feel seen, even decades after the shutter clicked.

If you haven’t yet fallen down a Rosemary Gilliat Eaton rabbit hole, I highly recommend it. You can type her name into the Library and Archives Canada search tool, or simply look her up online and see what comes up. I think you may find, as I do, that her work has a way of staying with you, like a heart-to-heart talk you keep thinking about long after it’s over.

*All photos by Rosemary Gilliat Eaton, courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

**The last photo in the gallery above is of Rosemary and her husband Mike Eaton, near Parliament Hill in Ottawa, on their wedding day.

**You can find out more about the fascinating life of Rosemary Gilliat Eaton here.